By Cleveland Moffett.

Originally published in McClure’s Magazine in March of 1899.

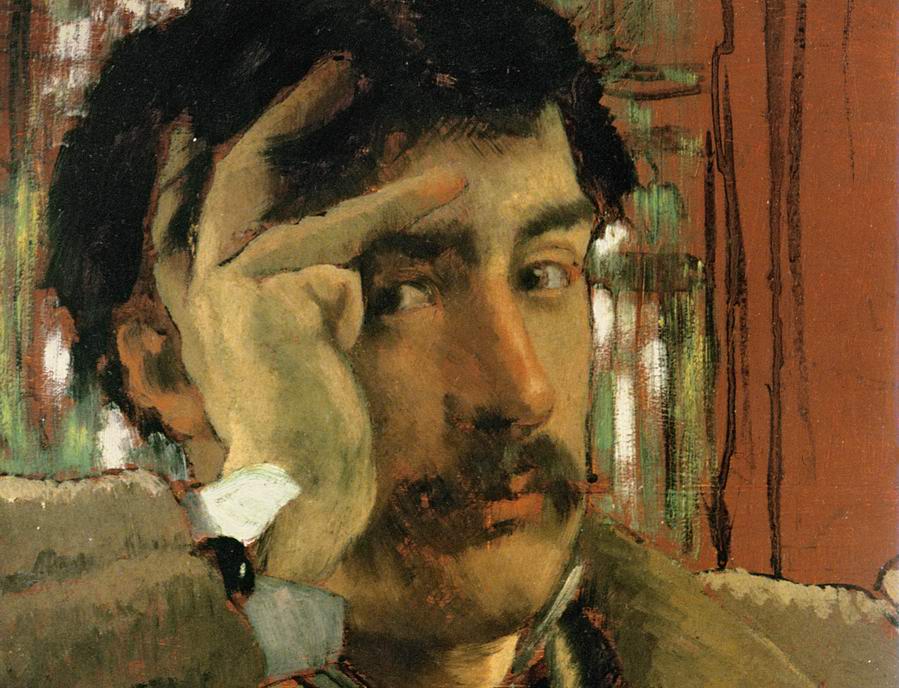

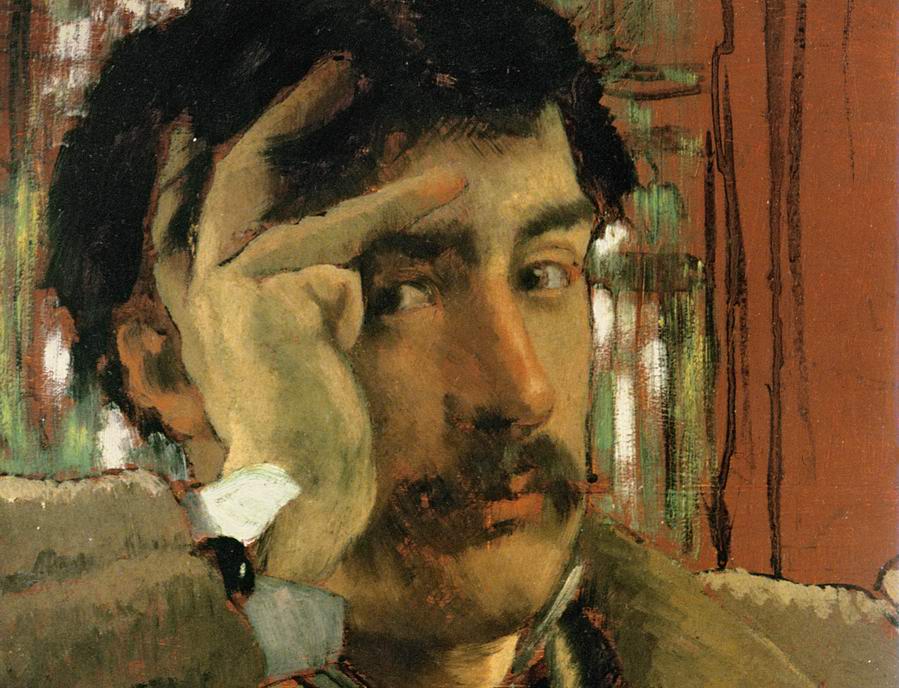

James Tissot. Self-Portrait (1865)

Monsieur James Tissot is now a man of sixty-two, yet his vigor of mind and body is remarkable. One might almost speak of his vigor of soul, for the spiritual quality in this distinguished artist is one of his most striking characteristics. Not only is he deeply religious in his daily life, but he is something beyond that: he is a mystic and seer of visions.

But the Tissot of today, the man of solitude and meditation, the reverent worshiper, the almost ecstatic believer in divine mysteries, is a very different Tissot from the one who left Paris twelve years ago to undertake a great work in Palestine. Up to that time Tissot had been known as an artist of unusual power and versatility, but an artist who was also much of a worldling. He was a traveler and a cosmopolitan; he was at home in many cities. Ten years of his life were spent in London, where he earned some millions of francs from his paintings and where his house was famous among grand establishments for the beautiful things within and without it. This was the house that later passed into the hands of Tissot’s friend Alma-Tadema.

It was from this brilliant and somewhat pampered life, from a circle of friends that counted the best names in Paris and London, from affluence and ease, that Tissot suddenly separated himself as he passed the half century point. From painting scenes of Parisian frivolity, he turned his attention to the old subjects of Bible story, to the humble scenes of Christ’s life. From gay salons he made his way to moldering churches. His city house and his splendid chateau in the country were given up, and he declared himself ready to spend months or years in poor and mean surroundings to the end that he might put down from actual observation scenes and incidents in the Holy Land.

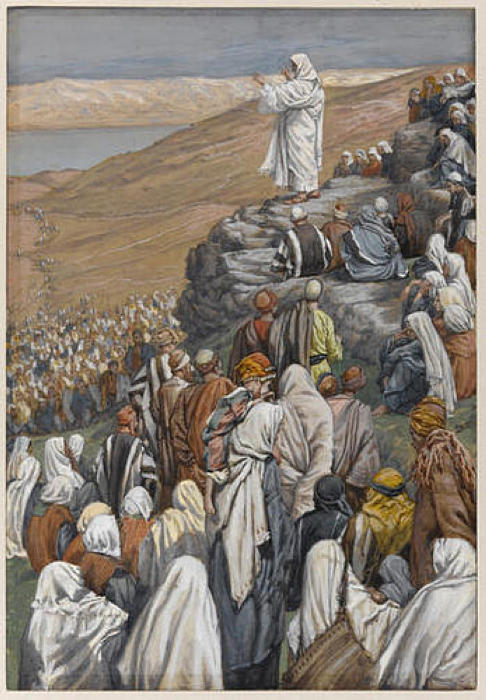

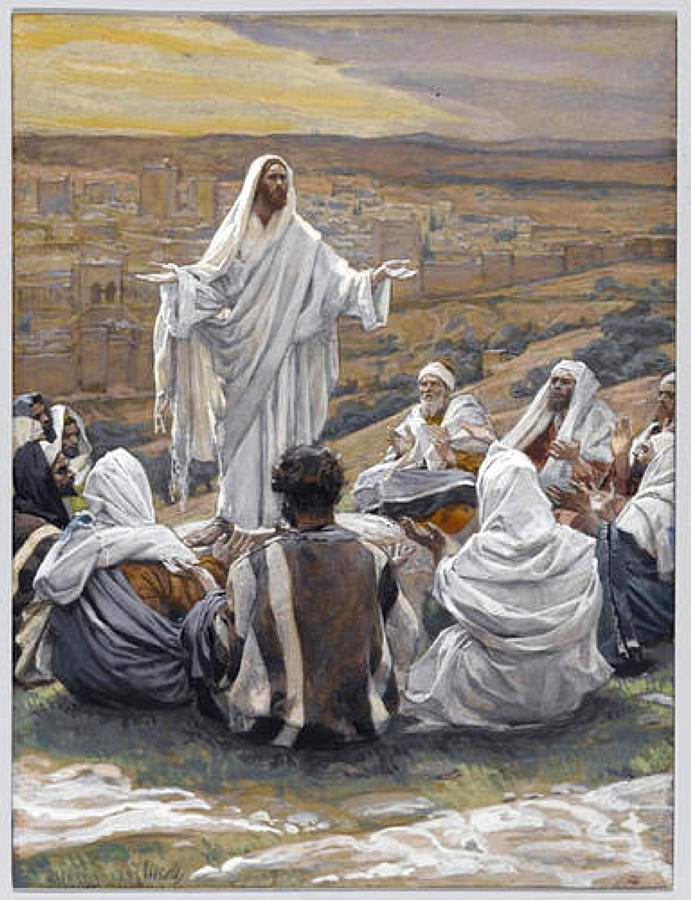

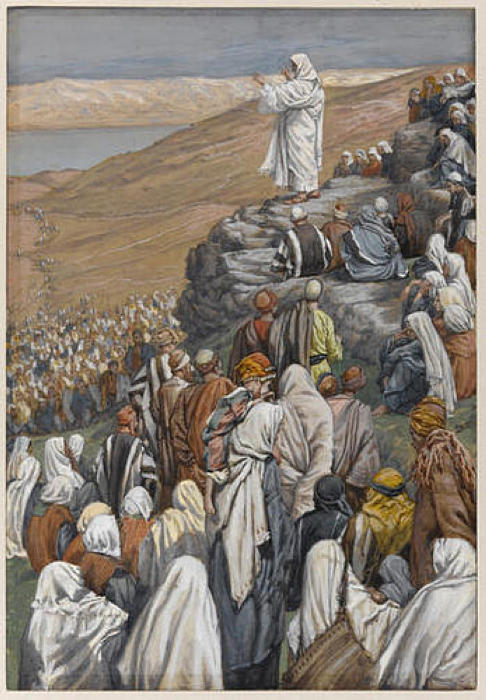

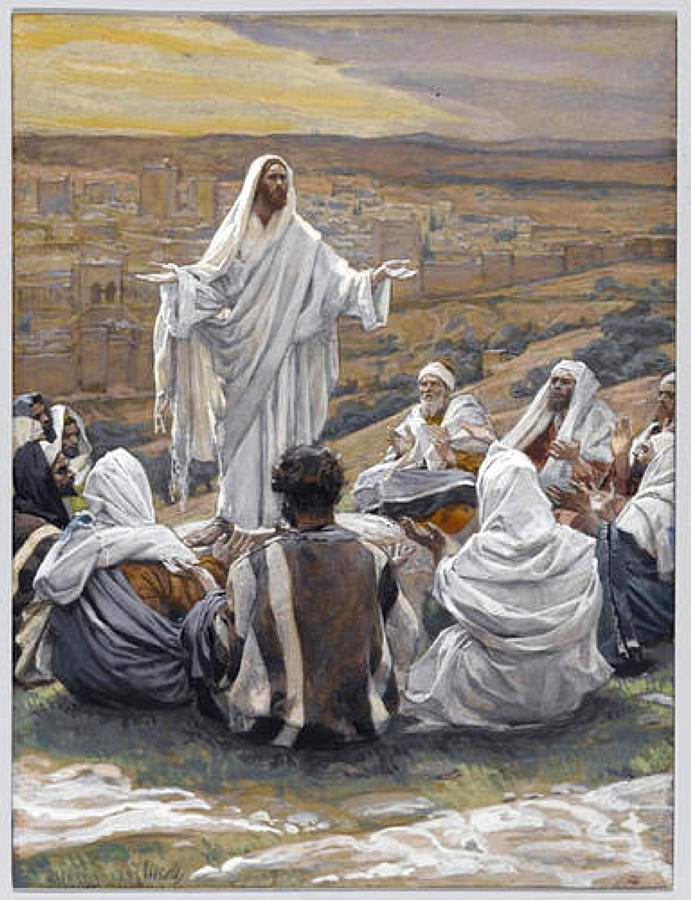

James Tissot. The Sermon on the Mount

The cause of this sudden change in a man of mature years was sought for eagerly by Tissot’s friends. There was much gossip about him in Paris and London. It was rumored that he had entered a monastery. There was no doubt that he went to prayer frequently, that he shunned the busy and frivolous paths once trodden by him with pleasure. People who had known him well saw little of him now. But why this change had come on, or just what it meant, remained in the realm of conjecture. It is sufficient for us to know that the death of a very dear friend about this time had much to do with turning M. Tissot’s thoughts in a new direction. He saw life more sadly and more seriously. He felt himself alone in the world, for he had never married, and with ebbing fires of the body, the soul fires began to burn more brightly. The worship of God was no longer a subject of speculation, but a real thing that had come into his heart. And now in the East a star of guidance shone out clear, a sign in the heavens beckoning this man, calling him to Jerusalem, and he heard the call and answered it. Tissot the artist became Tissot the pilgrim.

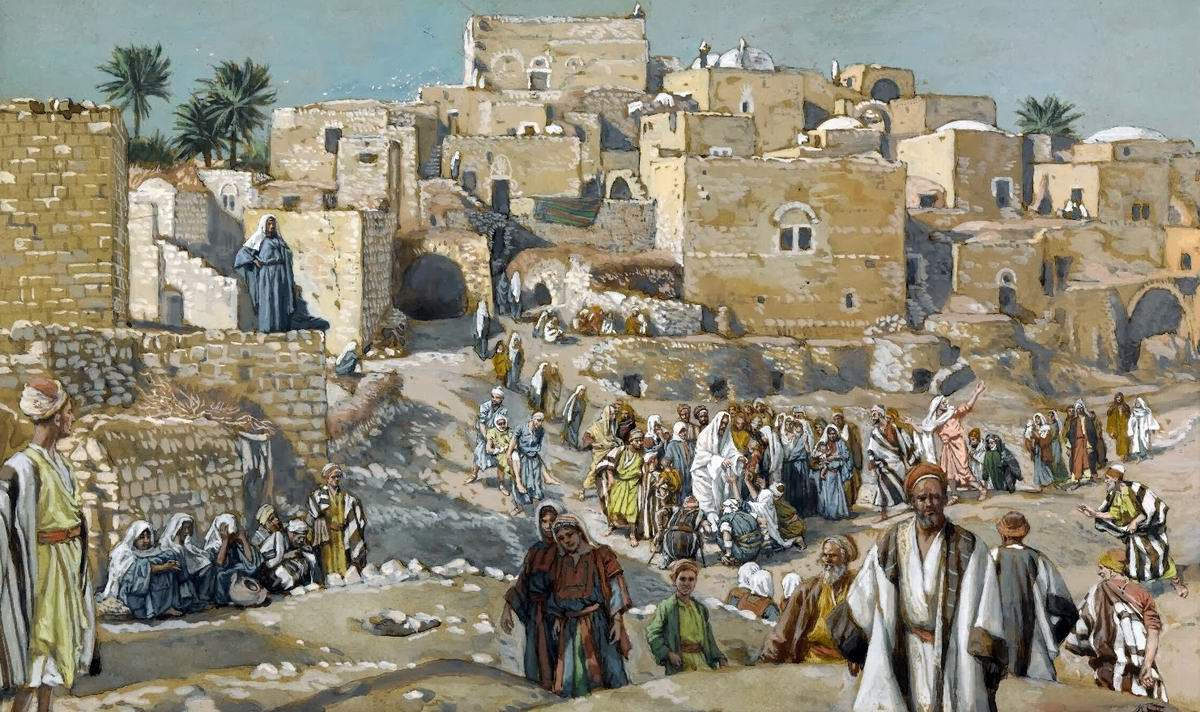

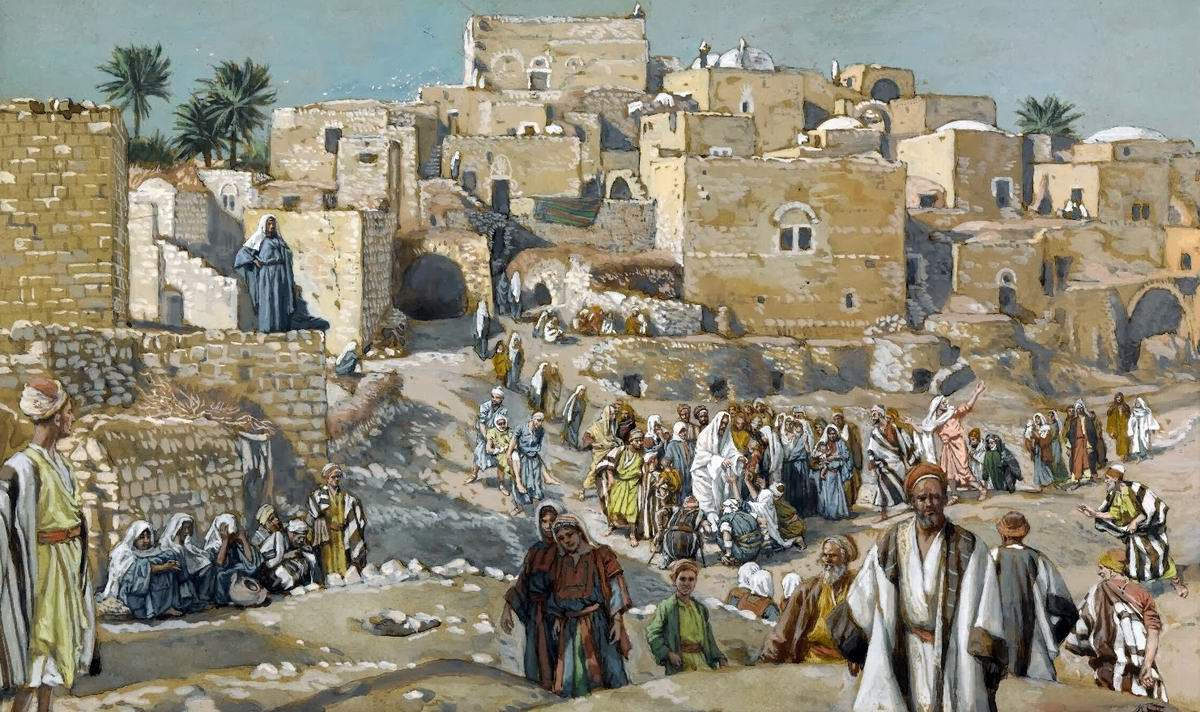

James Tissot. He Went Through the Villages on the Way to Jerusalem

It was in 1886, an afternoon in November, and a fine rain was falling on the bare plains of the Holy Land. Over the reddish earth, over the yellowish hills, a caravan wended its way toward Jerusalem. It was a small caravan, seven horses and two asses, with servants in native dress, and a dragoman in half-European dress, and a man who had brought these together for a great purpose. This man rode at the front of the line, and strained his eyes eastward. There was strength in his face and build, kindness and power in his eye; he was a man to think and hold his tongue. The gray hair over his temples and the grizzled mustache bore witness to fifty years gone, yet was he undertaking the labor of a lifetime; he was come to study and record with brush and pencil nothing less than the life of our Lord Jesus Christ.

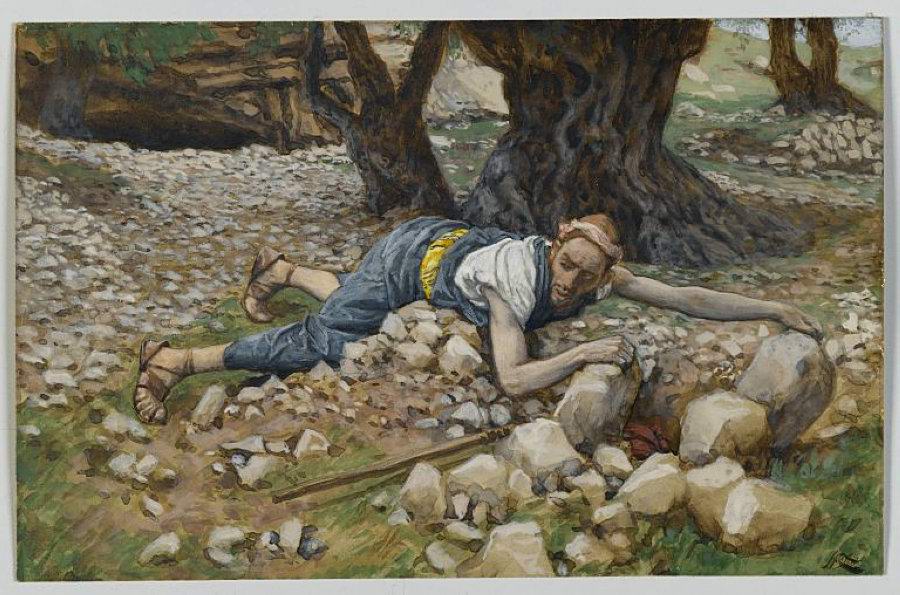

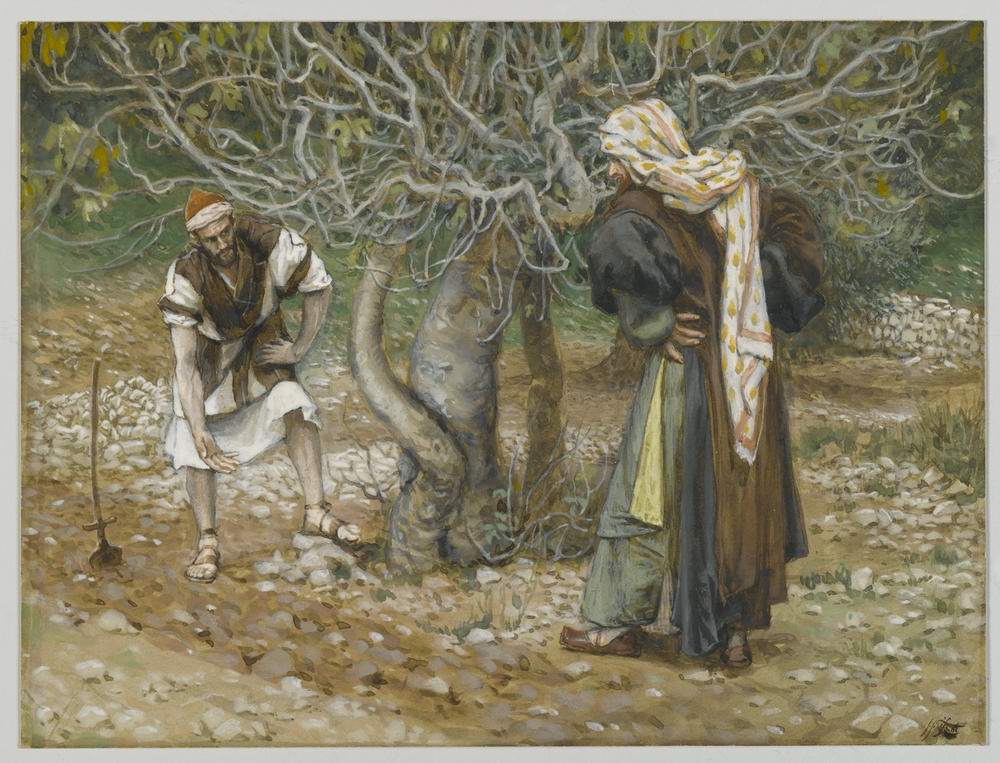

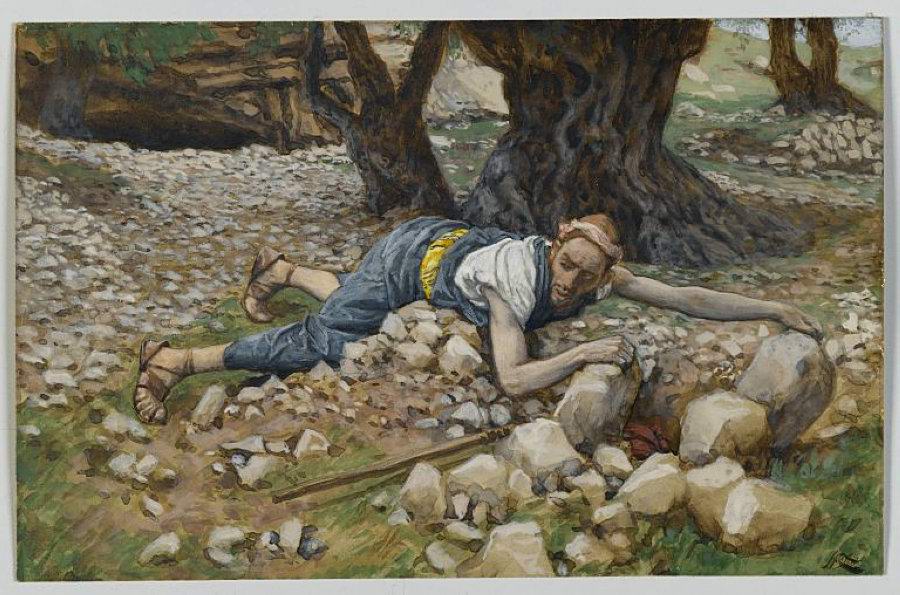

James Tissot. The Hidden Treasure

For two days now M. Tissot had been journeying toward the city which was to teach him so much that he might show it to the world. The night before, he had slept in the village whence according to tradition – came the robbers who were crucified with Jesus. The day before that, he had set out from Jaffa, the air filled with caroling convent bells that seemed to cheer him on his way. Before that, he had seen the land of Egypt, with its silent, black-clad women, its colors, its odors, its Pyramids, and its memories. Before that, he had gone with the pilgrims to Lourdes, to ask a benediction on his effort. And now Jerusalem lay before him, only a few miles distant.

It was about three o’clock when the dragoman rode up beside M. Tissot and, pointing ahead, told him that the Holy City lay yonder.

“Impossible!” exclaimed the artist. “I see no high ground there.”

“We’re going in by the gate of Jaffa,” answered the dragoman.

“You rascal,” exclaimed the Frenchman, shaking his hand in displeasure, “did I not charge you to bring me in by Mount Scopus?”

“It will take us an hour longer, sir,” grumbled the other, “and the horses are getting wet.”

James Tissot. The Lord’s Prayer (1896)

“What do I care! Do you think I have traveled two thousand miles to have my first impression spoiled? Do you think I have come here like a scampering tourist? Head your horse for Mount Scopus, sir, and learn to obey orders.”

The end of it was that the pack animals entered the city by the nearer way, through the gate of Jaffa, while M. Tissot and the dragoman made a detour in the rain, and came upon the vantage point selected by the artist, And for several miles M. Tissot kept his head turned resolutely away from the walls of the city lest a chance sight from some other than the point he had chosen for his first full view should spoil the picture that had been long preparing in his mind.

At last they stood upon Mount Scopus. It was the hour of the setting sun, and the rain had ceased. M. Tissot looked down upon Jerusalem spread before him, upon its domes and housetops, its vineyards and cypress trees. Then he turned to the south, and saw the Mount of Olives; and beyond that, stretching away in the distance, a broad line like purple velvet, changing into blue-black at the base; and across this line were blood-red streaks. It was the Mountains of Moab blotched with the sun’s last fire.

“And then I looked lower down into the valley,” said the artist, as he painted this scene for me in vivid words, “and I saw a mass of green, a wicked green, like a great emerald. It startled me as I looked at it, and I said to the man: ‘See, what is that – that strange green, under the blue-black mountains?’ ‘It is the Dead Sea,’ he said. And I stood still for a long time, staring at it.

“Then I turned back to the city, and as I looked, a white cloud shot high into the air and spread out like a silver tree in the sun, and there came a deep sound echoing through the hills. ‘See, what is that?’ I asked again. ‘They’re firing cannon from the Tower of David; it is a Turkish feast day,’ he answered.”

James Tissot. The Healing of Ten Llepers

To hear M. Tissot speak when he rouses himself thus is to be caught by the earnestness in him, the depth of feeling. What he saw from Mount Scopus this November afternoon had been seen there, no doubt, many times before by others; but perhaps no man ever saw it in the same way, or found such almost terrifying impressiveness in the colors. As he pictured those somber mountains over that wicked sea of emerald green, he seemed to shrink away as if from some sinister happening, and in his eyes the silver cloud over the Tower of David became a wonderful omen, yet it was but cannon smoke. It was plain to me, after the very briefest talk, that here was a man of exceeding sensitiveness and spiritual quality, one who believed first and painted afterward.

“I hope you are a Christian,” he said to me, with some hesitation. “If you are, it will be easier for me to tell you about my work in Palestine.”

Reassured on this point, M. Tissot went on to describe how on that first day he came down from Mount Scopus by a winding, stony path, passing through the Vale of Gethsemane, passing near the great Mosque of Omar, and finally reaching the inn where he was to stop. It was all very strange and terrible to him. He could scarcely eat; and, after the meal, he felt that he could not sleep until he had visited the Holy Sepulchre. So he made his way thither, through the dark narrow streets, and remained in prayer where Christ’s body had lain, until the guardians bade him go away, at the hour of closing. That was the first day of the work which it took him ten years to finish.

James Tissot. Ordaining of the Twelve Apostles-(1894)

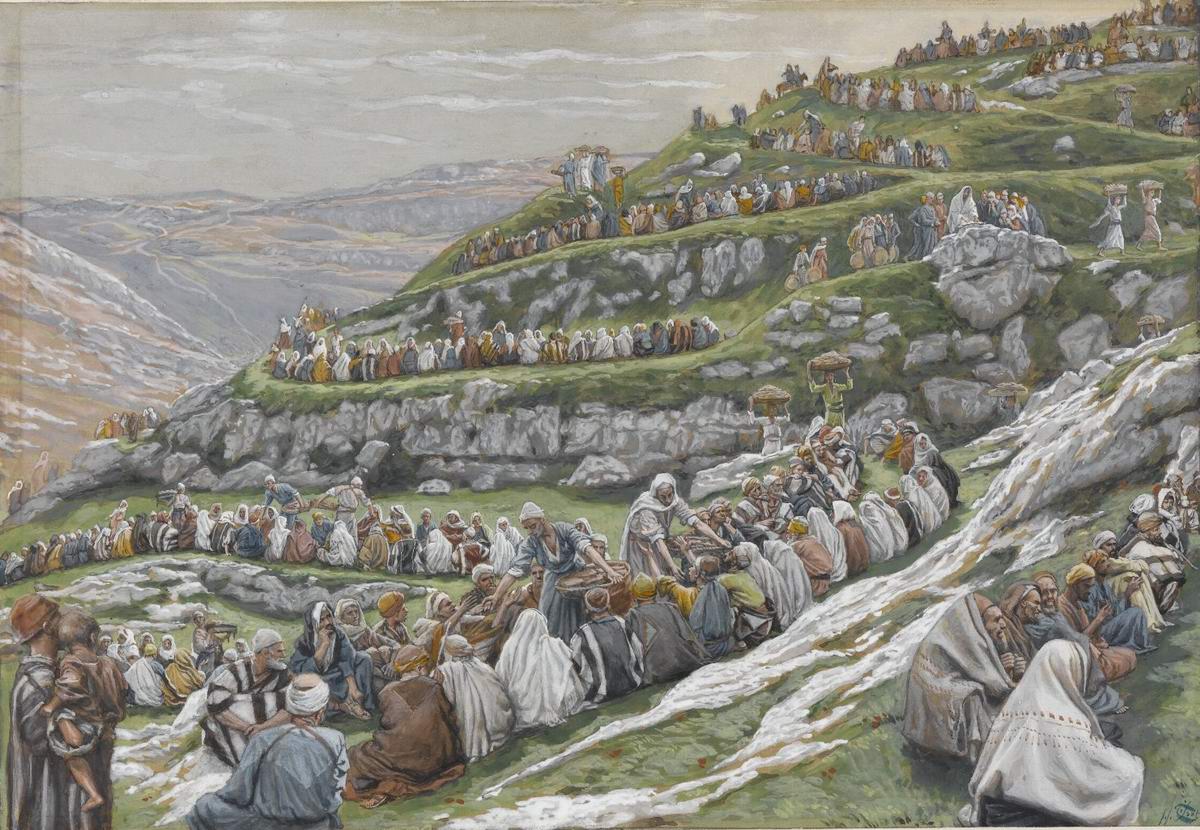

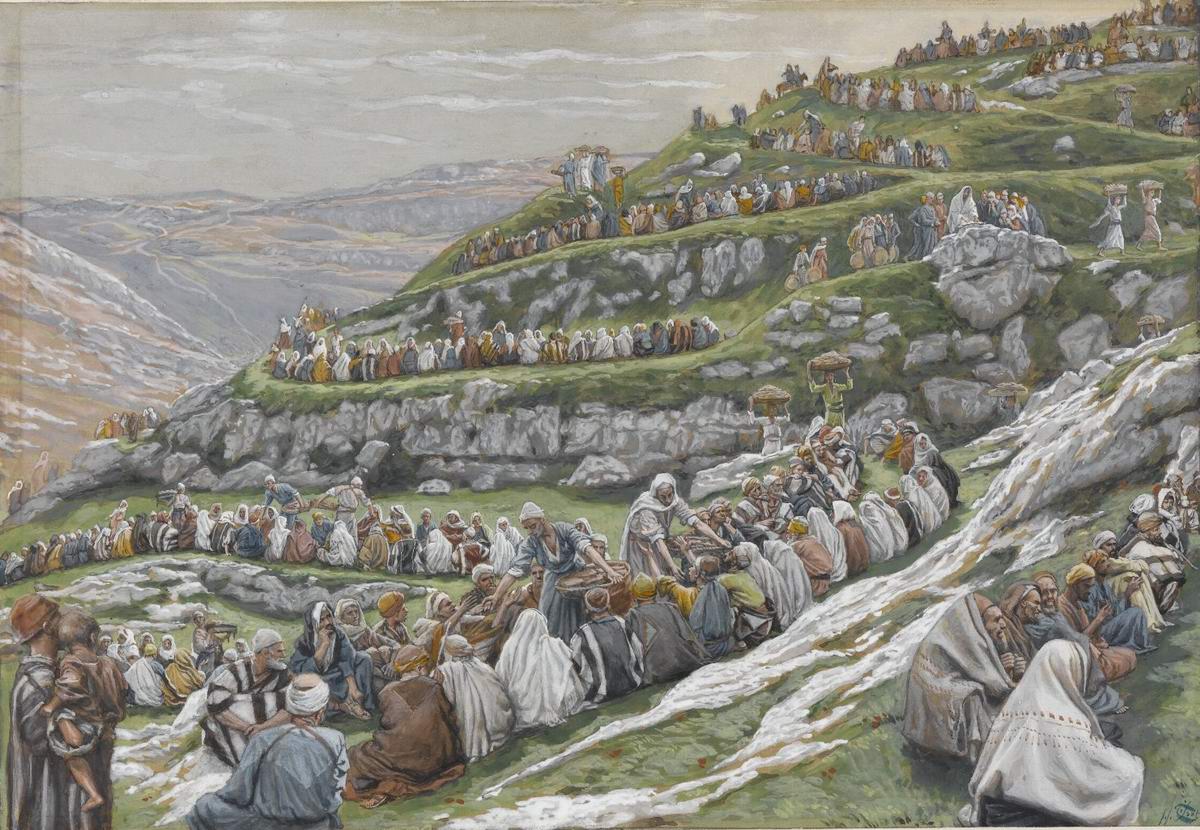

Ten years to do 500 paintings: so stands the record. And although these paintings, measured by inches, are not so very large, yet they present such variety of scene and incident, such knowledge of antiquity, such faithfulness in smallest details, such understanding of Oriental character, such convincingness in the setting forth of Christ’s ‘life, and withal such power of the imagination and spiritual insight, that one would think twenty years all too short for the task. What other artist ever painted one picture a week with merit in it and kept up that average for 500 weeks? Nor does this take account of hundreds of sketches done in preparation, nor of hundreds of initial letters and chapter endings and delicate bits of page decoration (two or three hours for each), done by this indefatigable man for the great French edition of his work just published. There was needed strength of soul as well as artistic power for this business!

A man of toil and prayer, then, was M. Tissot while in the Holy City. Six o’clock saw him out of his bed even on dark winter mornings, and seven o’clock found him at the Convent of Marie Reparatrice, bowing before the candles and listening to the chant of kneeling women. Fine ladies there are in this convent, young women who have given up fashion and fortune in European cities to serve in this lowly order. From his seat in the gallery where strangers sit, M. Tissot could see these sisters kneeling, their figures shrouded in garments of white and blue, a silver heart on the breast of each; and about the face, in square setting, two veils, one white, one blue.

“On the steamer I met three of these sisters,” said M. Tissot; “they were French ladies about to enter the convent. I remember asking one of them if her life was hard, if she was happy in renouncing the world.

“Oh, yes,’ she said, ‘I am very happy; we are all happy.’ And then she added, quite naturally, with a smile so sweet that it was sad. You know we die very young in our order.'”

James Tissot. The-Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes (1896)

In these surroundings he made his morning prayer, and then, after eating, set forth to work, riding through the streets of Jerusalem, a servant trotting beside him with colors and brushes in a basket, and a large umbrella for shade, and such other things as an artist needs. Then would come two hours’ sketching, the putting down of numberless backgrounds for the Christ story – a carpenter shop such as Joseph worked in, a mottled stone wall with worn steps down the face of it, some women drawing water at a well, a view from the Mount of Olives, a tomb, a cistern, a fig tree, and endless types of Jews.

Two hours of this, with an hour for journeying back and forth, brought noon; and then, after food and rest, came another excursion within or without the city, and two hours more of work. Nothing was too small for the artist to notice – the lattice screen over a window, a fashion of dressing the hair; and nothing was too large – the colors of a valley, the panorama of a city. What would serve his purpose he took down stroke by stroke, with infinite patience, using colors, using black and white, sometimes using the camera – whatever would give the best result. No trouble was too great. “Ce n’etait pas un travail, c’etait une priere” – “it was not a task, it was a devotion.” That was the man’s spirit.

After dining quietly, M. Tissot spent his evenings in reading and reflection. For the most part he was alone, and kept away from people who were rated important. He retired early, at peace with all the world, and however intense the emotions of the day, his rest was seldom broken. About the only work he allowed himself at night was the jotting down in an album of little pictorial notes, each one about the size of a postage damp, just the roughest pencil scrawling, to bring back a hint of composition. A half dozen such as these he did for me with a few quick strokes, and, as he did them, he explained that this was for “Christ before Pilate,” and that for “Angels Came and Ministered unto Him,” and so on. And even my untrained eye could see the suggestion.

Each one of these rude drawings might be called the receipt for a picture, and when the mood took him for painting, M. Tissot would enlarge one of these into a more detailed sketch, outlining the background and central figures in heavy black lines; the whole, still formless, the merest skeleton of a picture, with only black ovals for the heads and a few rough lines for the bodies.

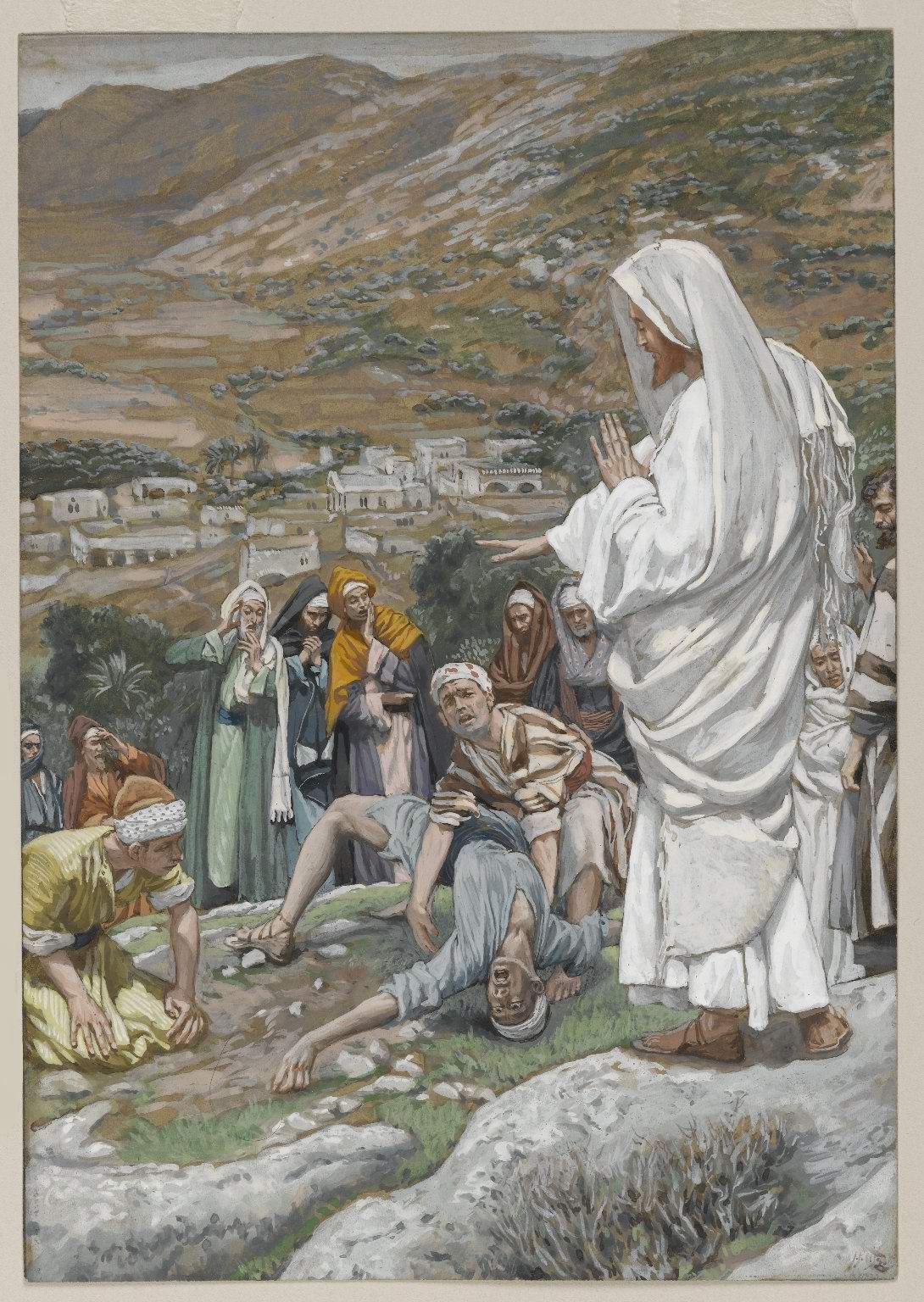

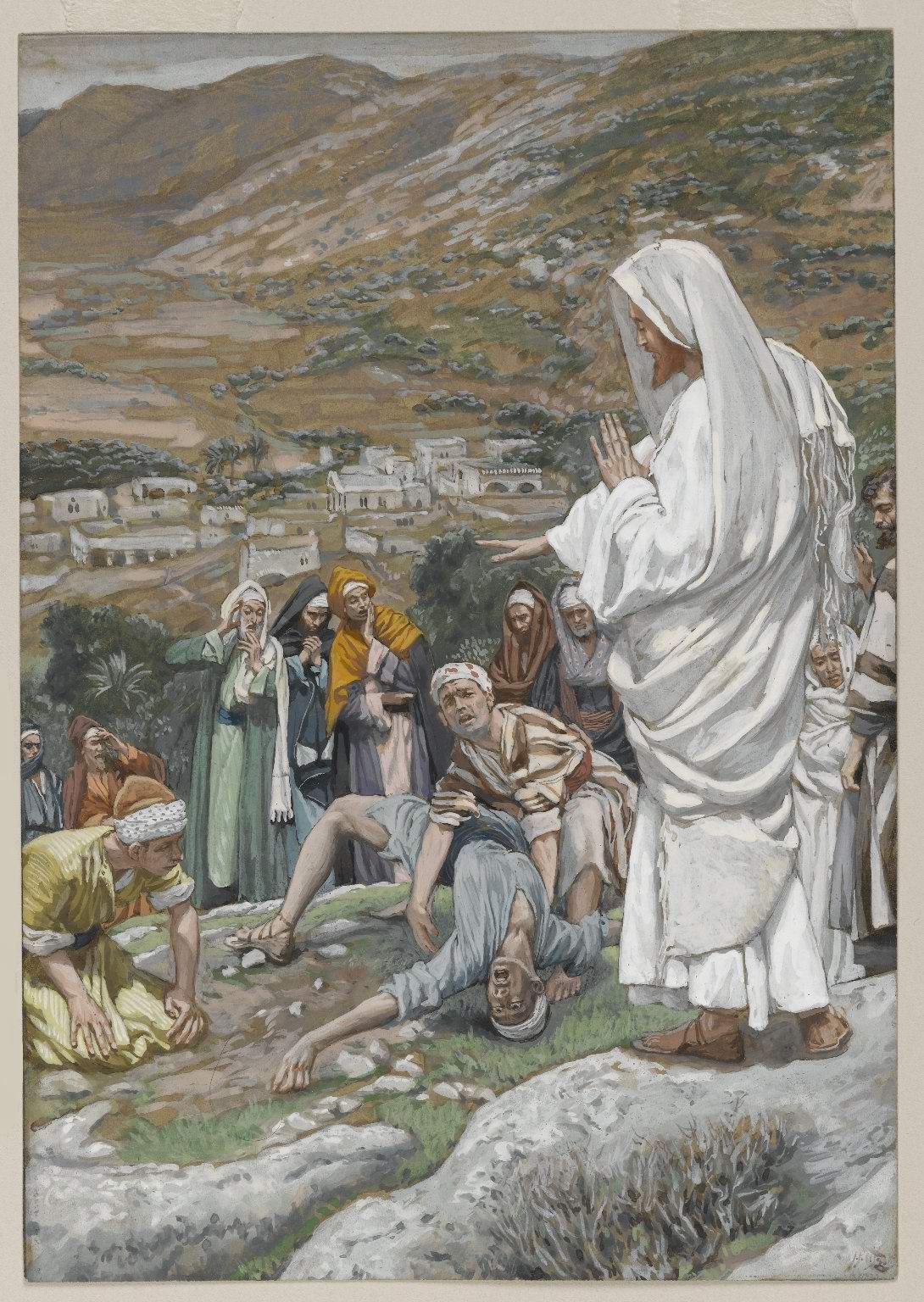

James Tissot. The Possessed Boy at the-Foot of Mount Tabor

But now a strange thing would happen, a rather uncanny thing, did we not know the many mysteries of the human brain. Scientists have called it “hyperaesthesia,” a supersensitiveness of the nerves having to do with vision. And this is it – and it happened over and over again, until it became an ordinary occurrence – M. Tissot, being now in a certain state of mind, and having some conception of what he wished to paint, would bend over the white paper with its smudged surface, and, looking intently at the oval marked for the head of Jesus or some holy person, would see the whole picture there before him, the colors, the garments, the faces, everything that he needed and had already half conceived. Then, closing his eyes in delight, he would murmur to himself: “How beautiful! How wonderful! Oh, that I may keep it! Oh, that I may not forget it! Finally, putting forth his strongest effort to retain the vision, he would take brush and color and set it all down from memory as well as he could.

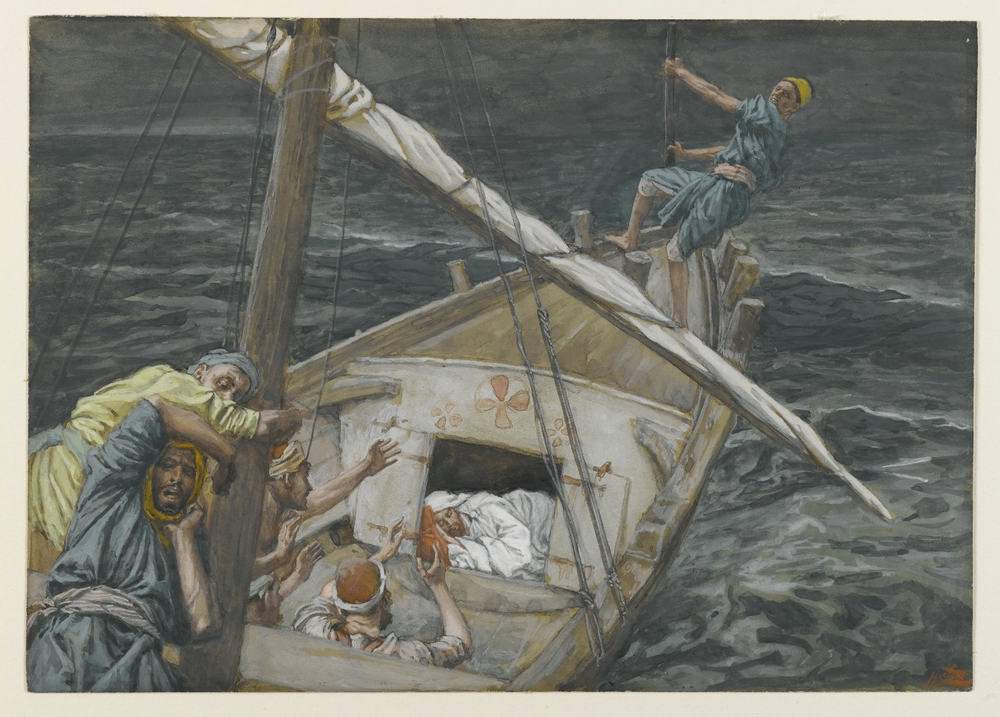

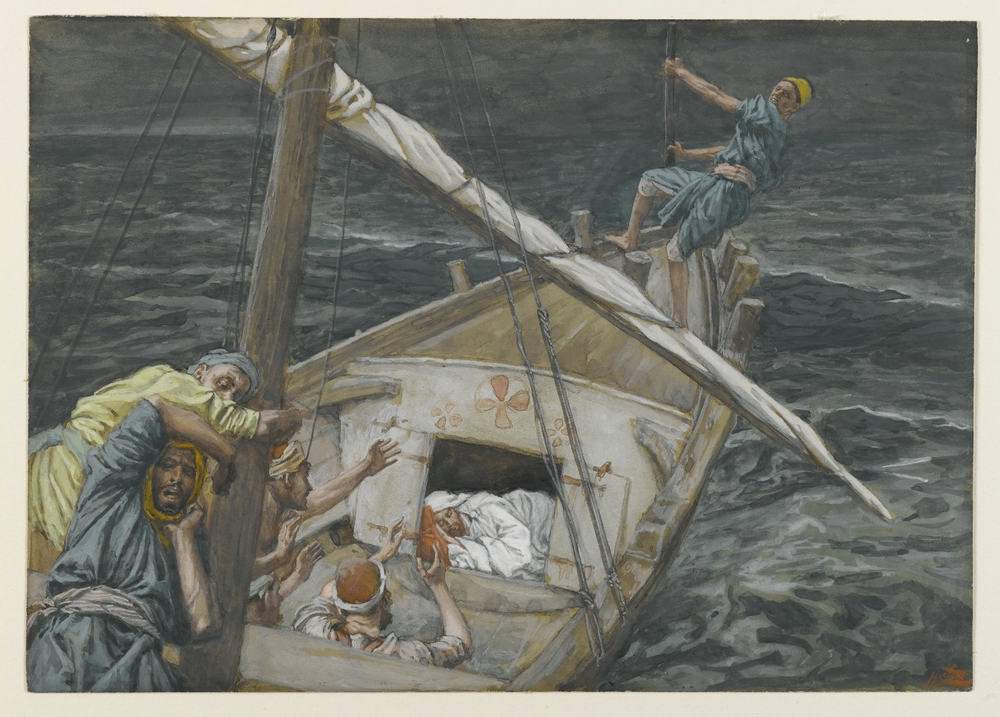

James Tissot. Jesus Sleeping During the Tempest

Most of M. Tissot’s pictures were painted in this way, at least in some part. But many of his best pictures were never painted at all, because the very gorgeousness of the scene made it slip from him as a dream vanishes, and it would not come back. “Oh,” he sighed, the things that I have seen in the life of Christ, but could not remember! They were too splendid to keep.”

Let me not give the idea that there is anything abnormal about M. Tissot. He simply possesses in a high degree the sensitiveness to color impulses of the brain that is enjoyed by many artists and gives them, literally, the power of beholding visions. It is a mere matter of cause and effect, just as certain dreams are induced by certain causes. In him the cause has been reflection and prayer and a peculiar artistic temperament. Not only does he get vivid impressions of his pictures from these skeletons of composition, but he gets them often while walking in the street; so distinctly, sometimes, that the real things about him seem to vanish. One day, for instance, while strolling in Paris, near the Bois de Boulogne, M. Tissot suddenly saw before him a massive stone arch out of which a great crowd was surging – a many-colored crowd – with turbaned heads and Oriental garments. And the multitude, with violent gestures, lifted their hands and pointed to a balcony high up on a yellow stone wall where stood Roman soldiers dragging forward a prisoner clad in the red robe of shame. Hanging down from the balcony was a piece of tapestry worked in brilliant colors, and over this the prisoner was bent by rough hands and made to show his face to the crowd below, and it was the face of Jesus. What M. Tissot saw in this vision he reproduced faithfully on canvas in his painting “Ecce Homo.”

And he did the same in many other paintings.

I asked M. Tissot one day how he got his data for painting the garments worn by Jesus. Had he seen these in visions, or had he found men in Palestine who dress today as Christ dressed ?

“I found men,” he replied, “who wear today such garments as Christ wore, but they were not in Palestine. They are a tribe of Arabs dwelling between Egypt and the desert to the north. You know the apostles bound their heads with turbans and wore colored garments like those found still in Judea. But Christ as a man dressed entirely in white – a white robe and white cloak. His head was never covered except by a fold of this outer garment. As a boy, Christ wore colors, like other boys, but when he became a teacher of men, one set apart from the rest, then he put on white. Only before Pilate and in the days of his trial and condemnation he was made to wear red, as a mark of his disgrace.”

“And how did you learn about Mary’s dress?” I asked.

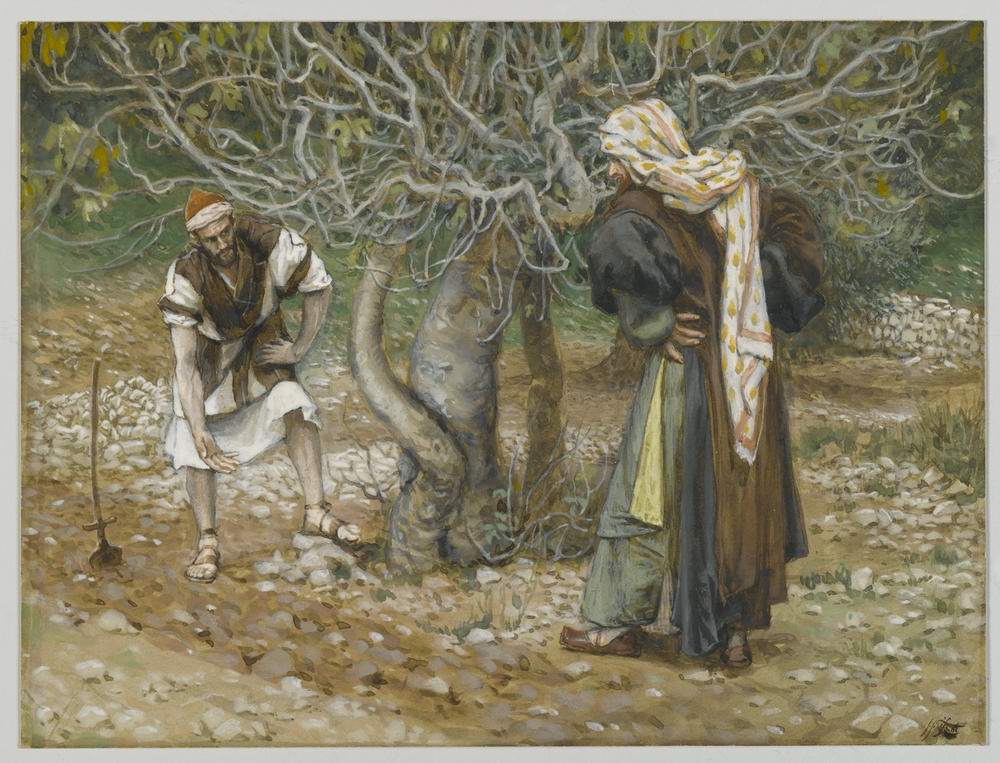

James Tissot. The Vine Dresser and the Fig Tree

“That was easier. The Syrian women in the vicinity of Bethlehem and in villages near Jerusalem dress to-day practically as the Virgin dressed. Their garments are made of striped cloth woven in widths of about one foot. The main part is blue, with a stripe of green at one edge, and a stripe of red at the other, and lines of yellow separating these from the blue body. A full width of this cloth forms the front of the gown, with a half width on either side. Then the fullness of the skirt is formed by a setting in of yellow cloth. The sleeves are flowing, the ordinary color being yellow and blue, and over all hangs a long white veil draped over a stiff headdress of red and green. The gown is held at the waist with a girdle of many colored threads – into which the front of the gown is tucked so as to form a spacious pocket. In this the women carry all sorts of things, including nuts, and raisins, which they are constantly munching.”

“Could you do much painting on these journeys?”

“Not while we were actually on the march; but I made many sketches in the villages, and took photographs which were useful as documents. Most of the actual painting of pictures was done in France. I would spend a few months in the Holy Land getting material, and would return to Paris to use it. Then I would go back for more, and then return again. In the ten years I made a number of these double trips, getting my vivid impressions in the one country and carrying them out in the other.

“To do my work best I must be able to think and feel quite alone, I must have solitude. So, for weeks at a time, I would withdraw from Paris to a wonderful lonely valley, shaped like a vast amphitheater, where the wind blows always and a little river runs. This is one of nature’s worship spots, where reverence is in the air. Hundreds of years ago godly men chose this place for a monastery, and on the ruins of their building I have made my home for contemplation. Ah, the days that I have spent there listening to the wind sigh and watching the river flow!”

James Tissot. Crucifixion Seen from the Cross (1890)

So it went on from day to day during the weeks that I had the privilege of being with M. Tissot. Each time I saw him he told me strange things. Each painting we spoke of became the subject of a little discourse. And there were 500 paintings. And there were ten years of thought and work and prayer. All this to talk about!

Originally published in McClure’s Magazine in March of 1899.

————————————————————————————-

comments